There is a

traditional zarqa table

that I found out about in Beth Owen's book (pdf is available here) - what a delight to be in conversation with someone I can learn from who

has summarized so much historical data so clearly already.

This quote on page 85 really struck me. 'Revell ultimately concludes that for

the Hebrew Bible, Rylands Greek Pap. 458 shows “clearly that the basis for the

system of cantillation represented by the later ṭeʿamîm was already firmly

established in the second century BCE and was so much a part of the formal

reading of the Torah that it was also used for the Septuagint.”' If this is so

then what happened to the tradition between the second century BCE and the 9th

century CE?

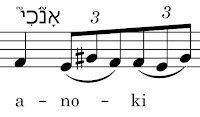

To allow the zarqa table to be more and more useful, we need to know what

ornaments are used with which recitation pitches. So I say to myself, there

are some dependencies among the te'amim. For instance, reciting notes govern

the starting pitch for any associated ornaments. Ornaments as a musical phrase

are relative to the current intonation pitch which itself is defined by the

last used accent below the text.

So I had to dig out more information from the text to see what sorts of

sequences are permissible. Also, I have to admit that although disjunctive is

an odd word for a cadence or even a pause in the music, a cadence does disjoin

one phrase from another. This all still appears to be approaching the music by

entering the room backwards.

Here's some of what I found: shalshelet never occurs with reciting note c, d,

f (prose), g, g#, or B. So in a zarqa table, one should not have shalshelet

following darga, tevir, galgal, merkha (21 books), d'khi, tifha, or munah. Or

put positively, shalshelet operates on merkha (in the 3 books), atnah and

yetiv or mahpakh (in all books). It occurs rarely in any case, 46 times in the

WLC data as far as I can measure -- 39 of them in the poetry.

Similarly, illuy, which can go into the stratosphere (high G if you can take

it) occurs most frequently governed by mahpakh. Illuy is more frequent -

occurring 191 times in the poetry, of these 88 are from the tonic - leaping up

for a syllable to the dominant, and 87 on the submediant, the 6th degree of

the scale and leaping up to the high G or down to the low g if that's easier.

SHV chose the low g in Psalms 1 and 137 - but in 137 I think the high g is

appropriate - it is a scream on the 9th verse reflecting that verb only used

twice in the psalms: Psalm 2:9 - you will smash them, where there is no

word painting at all, and 137:9 where the illuy paints the stress on

the smashing of the children's heads.

Just look at what trouble the zarqa table can lead you to. If the tonic

represents a lower tone of voice, the end of the verse is significant. How

could you possibly think this way!

|

|

137:9 one of the many beatitudes in the psalms

|

The long and short of it is that in this generic zarqa table following, I had to

switch key signatures for the shalshelet to the default mode for the three books

since it does occur twice on the merkha there, e.g. Job 37:12. The zarqa table

does not distinguish the two systems of signs. I have not included some repeats

from this tenor part nor have I included Mekarbel = munah, or Paseq (not

interpreted as music) or meteg/ga'yah. But it sounds as if the end could be a

cadence in a work for four parts -- so I expect the composer was showing his

capacity for writing. Good show!

|

Job 37:12 - one of two places in the poetry where shalshelet occurs on

an f#

Psalm 89:2 is the other one...

|

Here is the tenor man's table translated:

|

|

Zarqa table following the composite table in Beth Owen p 135.

|

The sequence in bars 5 to 9 is very common. Note the change in key

signature for the last line. There is no illuy in this composition.

This

has been an adventure -- I will return to it and try to see what else can be

considered about the relationship between recitation pitch and ornaments.