|

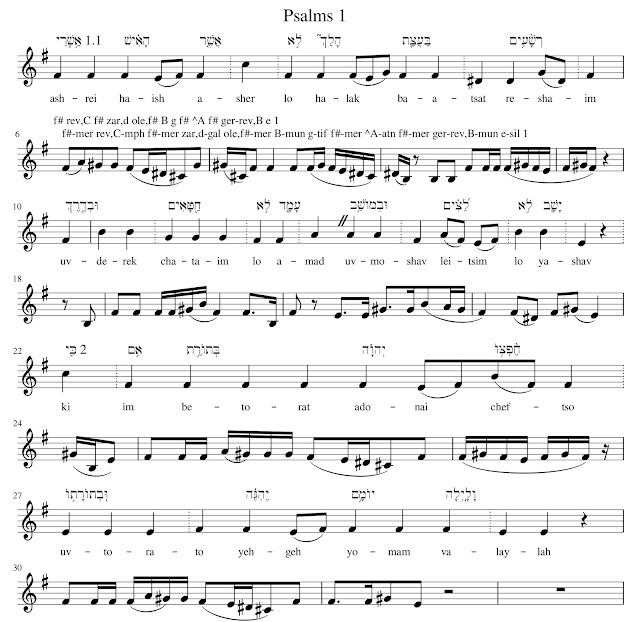

| Psalms 1:1-2 comparing cantilation interpretation, Haiïk-Vantoura vs Burns |

There is a lot to compare musically. SHV is in a different mode, Effectively E minor. Burns has chosen E major. This is fine. The choice of mode is moot. I could have transcribed SHV as E major.

I don't think that Burns considers any other mode, however. SHV varies the mode from psalm to psalm considerably. They could be accompanied by stringed instruments with variable tuning if needed.

Burns is very melismatic. I challenge you to map the notes to an accent. I listened to Psalm 96 and thought of transcribing that since the accents demonstrate the strophic form of the poem. I could not hear the strophes with the Burns version. The munah is lost as a marker of groups of verses. It is there in the text, but it is obscured by the slurs. I might be able to learn to hear it, but why make it so difficult?

It is remarkable that the lines begin and end on the same notes.

Less is more, I think, in this example. So let me see if the following will help identify the shapes of the accents more completely. The underlay may also help. I have marked the accents roughly as SHV interprets them. Her interpretation is unvarying and clear. An accent below the text always means move to this reciting note if you are not already there. An accent above the text is an ornament, distinguishable from the other ornaments.

So what notes are associated with the accents in the Burns melismas? I am out of my depth. He says there is a nasogh akhor to begin. The explanation floors me.

Nasogh akhor (retracting) is the frequent practice of displacing an accent to avoid an unaesthetic collision of two consecutive accents. It occurs when two consecutive words have a conjunctive and disjunctive accent, respectively, and the first word would be normally accented on its last syllable and the second word is accented on its first syllable.That is not the case in Psalm 1:1. So it is apparently an extended one. He also notes the accentual role of a metheg in the construction.

Here, the accent of ashre is moved from its normal ultimate position to the penultimate syllable, even though the following word is not accented of its first syllable, as would be the case in a conventional case of nasogh akhor. Thus, an artistic tension arises between the unusual accent on the first syllable of ashre and the next accent, which is distant from it - on the second syllable of ha'ish. The placement of methegh on the syllable that has lost its accent can be observed in this example. It is almost always present in the cases of extended nasogh akhor. This is understandable, since and extended nasogh akhor changes the normal pronunciation of words more radically than the conventional one, and therefore, the assurance that it is not unintentional is even more appropriate.I will say in my bias that metheg has nothing to do with the accent system. It is an aid to pronunciation of some vowels. The explanation in Lambdin is still confusing. It lists four different uses of a metheg. And their usage has grown over the past 1000 years. There are fewer in the Aleppo codex than editions up to 1950. I understand that later editions have recognized the value of the Aleppo codex more fully. (Not my area of expertise).

Nonetheless, the accentuation of the music is remarkably similar in the two interpretations. It might just be possible and a cool musical exercise to combine the interpretations in an overlapping multi-voice fugal motet. I might just try it some day. Psalm 1 is very beautiful. The traditional melody could provide an intriguing counter-subject.

|

| Psalms 1:1-2 comparing cantilation interpretation, Haiïk-Vantoura vs Burns with some annotation |

No comments:

Post a Comment